The Portsmouth Museum and Art Gallery is home to a fine depiction of a review of the Worcestershire Militia by Richard Livesay. The painting shows Major-General John Whitelocke, who later led a British army to ignominious defeat in South America, inspecting the corps on Southsea Common in October 1800 during the French Revolutionary War. A rare portrayal of an entire regiment drawn up in line, the artwork is of special interest to me on account of its detailed renderings of drummers and band musicians assembled on parade. Although the Reverend Percy Sumner published a brief description of the painting in the Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research in 1946, a recent visit to the museum gave me the opportunity to more closely inspect and photograph the canvas.

Livesay’s work neatly illustrates the visibility (to say nothing of the audibility) of regimental instrumentalists on parade. Although Dundas’s Rules and Regulations dictated that drummers and band musicians should form in the rear of infantry battalions when in close order, in open order the band was to be conspicuously positioned in front of the centre of the line, just behind the colours. The drummers were arrayed on both flanks ‘in order to make more show’, as the regulations put it. Livesay depicts just such a deployment, showing four fifers, four drummers and a drum-major on the extreme right of the line, flanked by axe-wielding pioneers on one side and the grenadier company on the other. Other drummers and fifers are deployed on the far left, although these far-away figures are harder to make out. The band in the centre appears to comprise some twenty performers – well in excess of the number officially permitted – and includes instruments such as bassoons, horns and the S-shaped serpent, not to mention a kettle drum and a bass drum. The painter depicts the band and the corps of drums playing and beating while officers and men salute the reviewing officer with their swords and muskets.

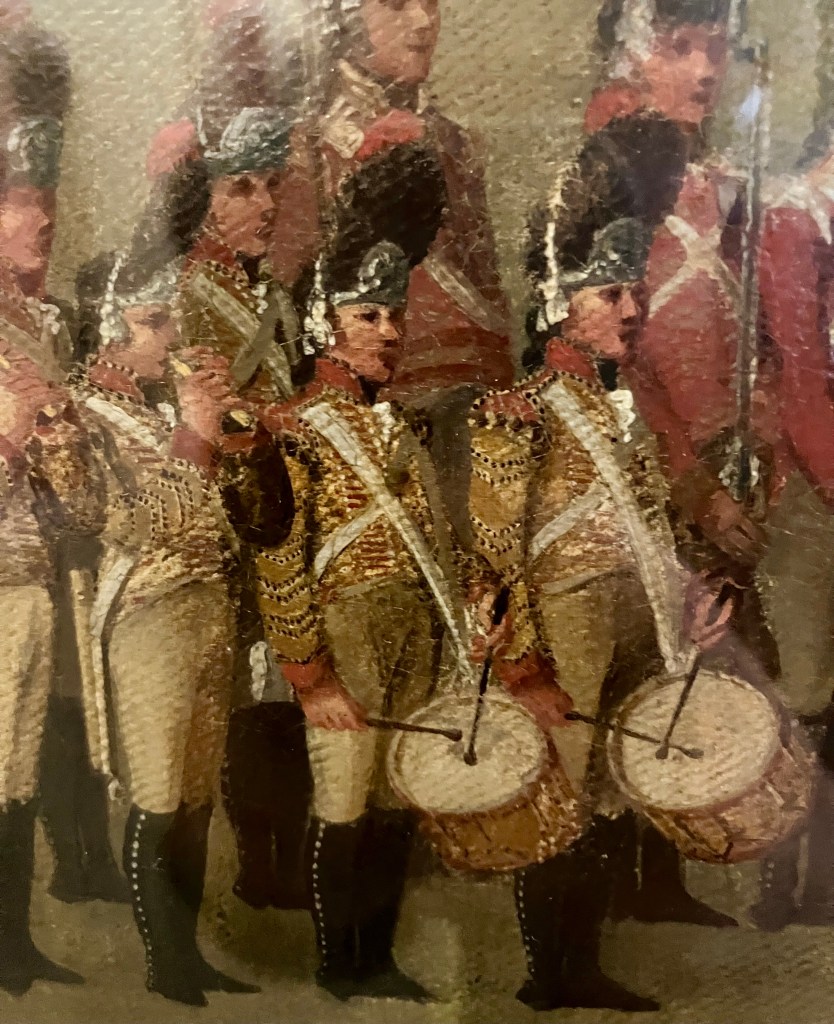

Drummers and band musicians were set apart from other soldiers not just by their functions and position on parade but also by their dress, which was especially splendid and typically of a different hue than that of the rank and file. Musicians’ clothing was not officially regulated, yet bandsmen tended to wear white uniforms; infantry drummers generally donned coats of their regiment’s facing colour – yellow, in this case. The drummers in Livesay’s painting, like the elite grenadiers and pioneers, wear large bearskin caps. Their coats are embellished with chevrons of distinctive polychromatic lace on the arms and what appears to be red hussar braid – an affectation normally associated with cavalry rather than infantry – down the front. Nor does the drum-major’s finery disappoint. Clad in a uniform which is buff or white rather than yellow, he bears his customary mace, sports a red cloth baldric (shoulder belt) adorned with silver-tipped drum sticks, and wears what seems to be the most ostentatious hat in the regiment. In view of such magnificent attire, it is hardly surprising that drum-majors were repeatedly mistaken for generals or foreign dignitaries.

Besides providing important visual evidence of the dress and disposition of drummers and bandsmen, the Livesay painting underscores the importance of these musical warriors for military display. The quantity, abilities, and clothing of drummers and bandsmen were preeminent points of unit prestige, regularly remarked upon by officers, newspapers, and civilian observers. By the final decades of the eighteenth century, regimental bands had become all but essential appendages of self-respecting corps. As a cavalry officer serving in Ireland remarked in 1784: ‘There is not a single Reg[iment]t of Infantry now in Ireland, nor any of Horse or Dragoons, who make a figure in the publick eye (which is no small matter toward the reputation of a corps) unprovided of this most necessary and ornamental show, a band’. The musical arms race only intensified as the British military grew to an unprecedented size during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. According to a sceptical Scottish clergyman writing in 1813, the militia regiments of Britain and Ireland ‘seem to have the foolish vanity of vieing with one another in nothing more than in the richness and fantastic dress of their drummers and military band.’ But the impact of such sustained investment in military music-making was not limited to bloated tailoring bills. The late Georgian military created significant new opportunities for musical employment and education while shaping and stimulating public musical taste. The wartime expansion of martial music-making facilitated the growth of the music profession as well as the formation of working-class brass bands. It even influenced popular politics: supporters of parliamentary reform, Irish self-government, and the Orange Order all mimicked military spectacle in the decades after Waterloo with the assistance of musically trained ex-servicemen. Military music, then, was not only prominent on parade but echoed far beyond the barrack gates.