The Battle of York is among the best-studied episodes in Toronto’s early history. Two centuries on, new information about this dramatic and traumatic event continues to emerge.

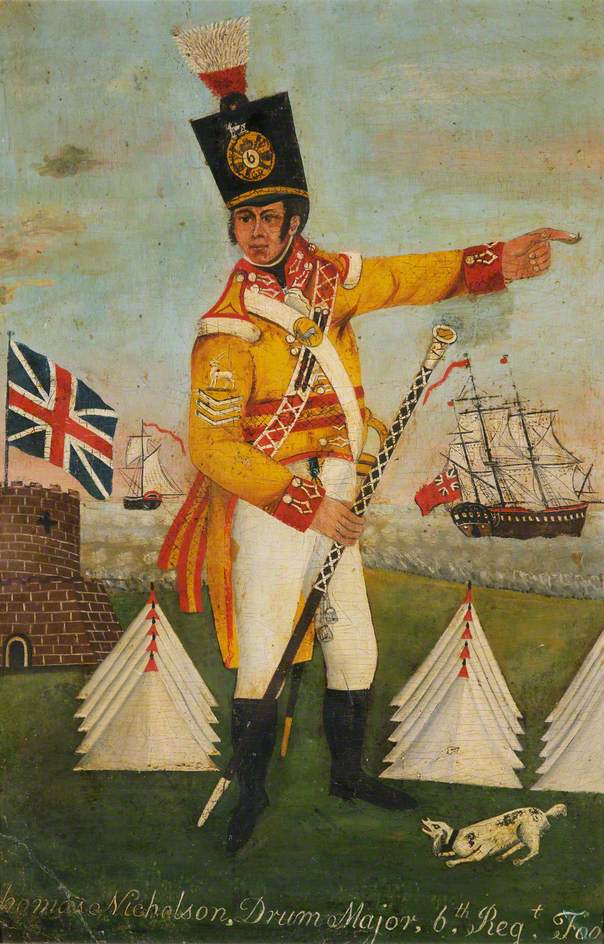

In a recent article for The Napoleon Series entitled Fops under Fire, I explored the experiences of British drum-majors in action during the early nineteenth century. These princes of pomp and circumstance were often ridiculed for their battlefield truancy, and indeed drum-majors were not expected to risk their skins by actively participating in combat. Rather than leading the band in stirring renditions of patriotic music under fire, most drum-majors occupied themselves with unglamorous yet essential tasks behind the lines, from aiding the wounded to haranguing would-be shirkers. However, a handful of brave (or reckless) drum-majors refused to confine themselves to such unadventurous auxiliary roles and were instead celebrated for their valour under fire.

One newly-discovered instance of drum-majorly daring took place at the Battle of York during the War of 1812. Having failed to check the invading American army on the beach or in the clearing at Fort Rouillé on 27 April 1813, the British fell back to the Western Battery near the site of the modern-day Princes’ Gate at Toronto’s Exhibition Place. Supported here by three artillery pieces, the defenders hoped to make a stand against the advancing enemy column. However, the accidental explosion of a portable powder magazine within the battery caused mayhem, dismounting all but one of the British cannons and killing or maiming dozens of men. The guns were abandoned as the enemy drew near, but according to an anonymous eyewitness account, in the form of an 1833 letter to the editor in the U.S. Military and Naval Magazine, the “gallant Drum Major of the 8th or King’s Regiment” returned in “full costume” to the stricken battery. At the very moment of “raising the linstock” to fire a parting shot from the remaining 18-pounder into the advancing American column, this “brave soldier” was brought down by a skilled rifle shot from Second Lieutenant David Riddle of the 15th U.S. Infantry. The drum-major was captured but was treated with “marked attention” in hospital on account of his courage and happily made a full recovery.

Yet regimental pay lists prove that the drum-major in question was not William Ankers of the 8th King’s, who was also present at the battle, but Thomas Kelly of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. The American confusion is, however, understandable given that the two corps, both royal regiments with blue facings, sported near-identical uniforms. Kelly, born at St. John’s in Newfoundland and approximately twenty-five years of age at the Battle of York, first joined the army in 1798 and had served for a dozen years as a drummer before his appointment as the regiment’s drum-major. Described as having grey eyes, brown hair, and a fair complexion, he was wounded and taken prisoner at the Battle of York but was soon released in a prisoner exchange. Kelly served as drum major until the Royal Newfoundland Regiment was disbanded in 1816.

Although the American correspondent claimed that “no one who witnessed the occurrence will forget” the sight of Drum Major Kelly’s fall, no other accounts of his battlefield bravery have been found to date. Even if Kelly had managed to fire a parting shot from the Western Battery, it probably would not have wrought much damage as the artillery piece was aimed too high to inflict serious injury on the advancing enemy column. Indeed, another American eyewitness recalled that the round shot fired from this gun failed to do more than clip the tops of their pikes and bayonets.

Nonetheless, the heretofore unsung bravery of Drum-Major Kelly during the Battle of York is worthy of our belated recognition. Although some drum-majors may have made themselves scarce under fire, as the sneers of contemporary memoirists suggest, Kelly proved himself worthy of his office and regalia on the battlefield as well as on the parade square.

Researched and written by Eamonn O’Keeffe

“Thomas Kelly: A Drum-Major at the Battle of York” was first published in the Fort York Fife and Drum in September 2016