This week I gave a speech in London at a dinner commemorating the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. I have decided to share an edited version of my remarks, which were delivered in my capacity as a National Army Museum research fellow, to mark the 265th anniversary of the battle. I have also included a brief list of books at the end of the post for readers wishing to learn more. – Eamonn O’Keeffe

The 1759 siege of Quebec, of course, enjoys particular prominence as a turning point in Canada’s past. But it also remains a storied episode in military history on both sides of the Atlantic. This should come as no surprise, for quite apart from its profound repercussions, as C.P. Stacey observed long ago, the truth of the campaign’s climax seems almost stranger than fiction. There’s the hushed, suspenseful transit across the St Lawrence River; the nocturnal clambering up the cliffs; and the mortal injury of both commanders in a brisk showdown before the city walls. It all feels like a scriptwriter’s flight of fancy – the somewhat rushed wrapping up of a television series.

And the news certainly felt incredible to observers at the time, not least because tidings of victory arrived in England hot on the heels of an earlier, despairing despatch from Major-General James Wolfe, which seemed to foreshadow a humiliating withdrawal.

In June of 1759, Wolfe had cruised down the St Lawrence aboard a flotilla of forty-nine warships and one hundred and nineteen transport and supply vessels. Aged thirty-two and entrusted with his first independent command, the general arrived with great hopes of success. But the end of August found Wolfe no closer to conquest, his many plans frustrated by the forbidding geography of the capital of New France and the resolve of its garrison. The defenders – comprised of French soldiers, indigenous warriors, and Canadian militia, headed by the Marquis de Montcalm – outnumbered his own army. They were well-entrenched on the Beauport shore downstream from the city: an attempt to land grenadiers and storm Montcalm’s lines at Montmorency on the 31st of July proved a bloody fiasco. Wolfe was reduced to launching desultory raids, bombarding the city, and laying waste to farms and villages in an impotent attempt to draw Montcalm out into open battle.

Time was running out, for the fleet would soon need to sail away to avoid being trapped by winter ice. Wolfe had already resolved to leave the army after this campaign; now he reckoned with the likelihood of defeat and disgrace. Only two years earlier, the Royal Navy had executed an admiral for failing to do his utmost – this was an age when performance reviews had teeth.

Wolfe was ill and often bed-ridden, plagued by dysentery, bladder stones, and fever. His relationship with the brigadiers, his senior subordinates, was just as dire. As one of them complained: ‘General Wolf[e]’s health is but very bad. His generalship…is not a bit better.’

But by early September, Wolfe had regained his nerve. He took the brigadiers’ advice to bypass the strong downriver defences and strike upstream of the city instead, in the hope of severing Montcalm’s supply lines. Yet almost at the last moment, Wolfe modified the plan. Rather than disembarking troops more than twelve miles upriver, he would target the Foulon cove, a place he had identified as a landing site of last resort weeks before. Though at the base of a fifty-three-metre escarpment, the cove was within two miles of the city and appeared, at least from a distance, to be lightly defended. Wolfe insisted on the change over the objections of his brigadiers and even the naval officer overseeing the amphibious operation. The gambit was a daring one, but it worked. Just after four in the morning on the 13th of September, Wolfe’s army began splashing ashore. They made their way up the slope and formed on the Plains of Abraham in the morning light.

It’s been said that celebrities who die young are given the benefit of many doubts, but historians – ever a disputatious bunch – are not so magnanimous.[1] Once lionised as a military genius, Wolfe has more recently been cast as a commander who was out of his depth and owed his victory more to luck than skill. He has been robustly criticised for his months of apparent indecision, his choice of terrain on which to fight, and his preference for the Foulon cove over supposedly less risky options farther upstream. Some scholars have even claimed that Wolfe had a death wish, and did not really expect the landings to succeed at all.

The debate has been lively and stimulating, but I think that many – though not all – of these arguments are overdrawn. As one of Wolfe’s more sympathetic biographers has trenchantly remarked, few generals have endured so much criticism for actually winning a battle.

Wolfe himself observed that ‘in war something must be allowed to chance and fortune’, and luck certainly played an important role in the campaign’s outcome. The French placed too much faith in the natural impregnability of the cove, neglecting to defend it sufficiently and failing to respond rapidly to the British incursion. Wolfe’s fortunes were also aided by the fact that sentries ashore initially mistook the landing craft for a friendly supply convoy they had been expecting – a misapprehension which was reinforced by the fluent French of a quick-thinking Scotsman in the British boats.

But to focus unduly on chance, and the mistakes of an opponent, risks obscuring the real achievements and professionalism of the armed services which made success possible two hundred and sixty-five years ago.

The British Army, which had so often come to grief in the early years of the Seven Years War, demonstrated its ability to improve and adapt. The redcoats became more inured to skirmishing in the North American wilderness, forming skilled marksmen into specially equipped light infantry corps. It was the light infantry which led the landings at the Foulon cove, dashed up the heights to overwhelm the French picket, and helped cover the army’s flanks during the ensuing battle. The redcoats had also learned to deliver disciplined firepower in the linear warfare which ultimately decided the day. They adopted the simplified firing protocol favoured by Wolfe and honed their aim through regular target practice. On the plains, British soldiers loaded two balls in their muskets and delivered devastating short-range volleys, routing Montcalm’s impetuous and ill-coordinated attack in a matter of minutes. Finally, lessons learned the hard way early in the war resulted in major improvements to amphibious operations. Sailors rowed soldiers ashore in flat-bottom boats purpose-built for use in shallow water; while shoals and strong currents still posed dangers, assiduous training and the use of signals and staging areas mitigated the risk of confusion and calamity. The Foulon landings, carried out in silence and under the cover of darkness, are rightly remembered as an exemplar of combined operations.

As the importance of amphibious capabilities suggests, it was the support of the fleet, under the competent command of Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders, which enabled Wolfe to strike at the heart of New France in the first place. Navigators such as James Cook, the future explorer, took soundings and drafted the charts necessary to allow the navy to ascend the hazardous St. Lawrence. Besides providing vital strategic mobility, sailors also helped distract from the Foulon operation by rowing noisily about in the darkness to deceive the French into thinking that the main British blow would land elsewhere. And, in the days after the battle, naval crews hauled over one hundred mortars and cannon up the heights to help besiege Quebec. Saunders even managed to raise more than £3,000 from his own officers as a loan to the army, which after accepting the city’s surrender found itself embarrassingly short of funds. This was a sterling example of interservice cooperation – I just hope the naval officers were paid back.

And more generally, it was the navy’s hard-won supremacy at sea which ensured that the conquest would stick. By the spring of 1760 the tables had turned: now a French force from Montreal was besieging the half-starved and sickly remnants of Wolfe’s army inside Quebec. Both sides turned their eyes to the river, knowing that success would come to whichever received fresh supplies and reinforcements. British ships began to arrive in May, and the Royal Navy destroyed an enemy convoy soon after, shattering hopes of a French recovery. Had the first vessels sighted borne Bourbon colours, Wolfe’s victory might well have been reduced to a historical footnote.

But as it turned out, the Quebec campaign marked a momentous milestone in Britain’s emergence as a global and imperial power. French Canadians are proud of the resilience and vibrancy of their Francophone culture, but the events of 1759 meant that English would become North America’s most spoken tongue. They also paved the way for the creation of the United States. With the Atlantic colonies no longer fearful of French neighbours, independence became a more feasible prospect; British efforts to reform, tax, and garrison their dramatically expanded domains gave rise to disagreements that sparked revolution.

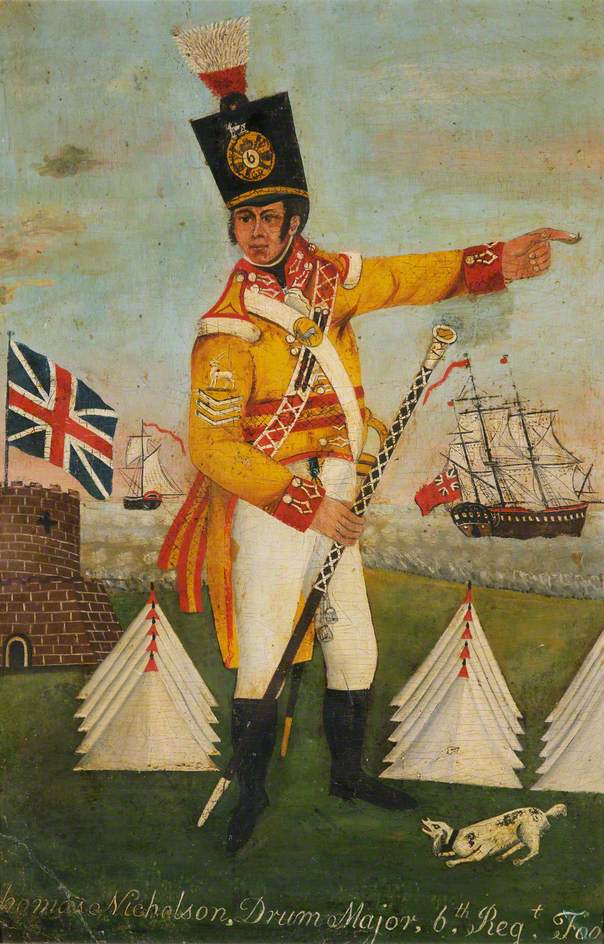

Anniversaries offer us opportunities to reflect and remember – Je me souviens, to use the Québécois phrase. To remember James Wolfe certainly, but also Saunders and his sailors and marines. To think of the French soldiers fighting for their country; the Canadians and indigenous warriors who were defending their land and homes; and the inhabitants who suffered grievously during the siege. Nor should we forget the officers and men of the British army: the Highlanders of the 78th Foot, who charged with their broadswords at the end of the battle, scarcely a generation after their kinsmen had rallied to the Jacobite cause; the North American subjects of the Crown, who comprised fully one-third of Wolfe’s besieging army; and private soldiers such as John Bell, a weaver from Antrim, and Thomas Clyma, a Cornish tinner, who fought and died outside Quebec’s walls. We are still living in a world they helped forge.

Further Reading:

Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (2001)

Stephen Brumwell, Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, 1755-1763 (2002)

Stephen Brumwell, Paths of Glory: The Life and Death of General James Wolfe (2006)

Phillip Buckner and John G. Reid, Revisiting 1759: The Conquest of Canada in Historical Perspective (2012), including Stephen Brumwell’s chapter on Wolfe’s generalship at Quebec

D. Peter MacLeod, Northern Armageddon: The Battle of the Plains of Abraham (2008)

C.P. Stacey, Quebec, 1759: The Siege and the Battle (1959 and subsequent edns) – a classic account

[1] Ian K. Steele, review of Paths of Glory: The Life and Death of General James Wolfe by Stephen Brumwell in The International History Review, vol. 30, no. 1 (March 2008), pp. 127-129.